Journalists covering Northern California’s 6.9 Loma Prieta earthquake will never forget the 1989 disaster. In print and on the air, their thoughts and insights brought the scope of the quake to life — and may again ring true when the next “Big One” hits.

By Jim Toland

Few people living in Northern California 30 years ago will ever forget what became the longest 15 seconds of their lives — a rumbling horror that killed 63 people, injured 3,757 and left behind more than $6 billion in property damage.

For many Northern California print and broadcast journalists, photographers and other media, the event became the epicenter for careers. This Media Museum report reflects on some of their in-the-moment thoughts, insights and published comments at the time. Read technical details and data about the quake here.

For many Northern California print and broadcast journalists, photographers and other media, the event became the epicenter for careers. This Media Museum report reflects on some of their in-the-moment thoughts, insights and published comments at the time. Read technical details and data about the quake here.

“People often ask, ‘How can I tell when there is an earthquake?’ and Californians always answer: ‘You will just know. You will know,’” San Francisco Chronicle reporter Carl Nolte explained in the aftermath of the ’89 disaster.

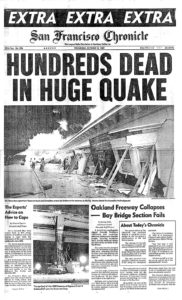

The magnitude 6.9 earthquake ripped along the San Andreas fault at 5:04 p.m. on Oct. 17, 1989, destroying a section of the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge, forcing the collapse of a half-mile section of Interstate 880 in Oakland, and igniting fires in San Francisco, Oakland, Berkeley, Santa Cruz and Watsonville.

The freeway collapse killed 42 when its upper level crashed onto the cars below. Another person was killed when a section of the Bay Bridge upper deck collapsed onto its lower level. In the end, the final property damage tally would include more than 12,000 homes and 2,600 businesses.

The temblor and its two immediate aftershocks, centered in the Santa Cruz mountains about 70 miles south of San Francisco, became known as the Loma Prieta Quake, named for one of the nearby peaks. The quake, originally designated 7.1 on the Richter Scale was soon rescaled to 6.9.

Robert Maynard, Oakland Tribune editor, reflected at the time: “Nature has a way of reminding us of the overwhelming power and force that shaped the universe. We felt 15 seconds of that force. We are all sobered, humbled and perhaps matured by what we saw.”

Panic at the World Series

The quake struck as more than 60,000 baseball fans had poured into San Francisco’s Candlestick Park to watch the third game of the World Series featuring the Oakland Athletics and San Francisco Giants (the scheduled game was postponed and Oakland would eventually sweep the Giants 4-0).

Just prior to the 5:30 game, with live TV cameras on the field, some of the nation’s best photojournalists flanking them and an impressive contingent of reporters in and around the press box, the rumbling began. The stadium withstood the shaking as panicked players and fans crowded the field.

UPI reporter William Murray was at Candlestick Park when the first jolt hit. “Phones immediately went out and the sky went dark from power outages. Despite harrowing circumstances, no panic swept the stands. Fans stood looking at each other wondering what to do. Each aftershock caused concern to grow more and more.”

“Let it be noted, this was the first time a stadium, not the fans, did ‘The Wave,’” Dick Draper of the San Mateo Times said before word of death and damage began to filter through the crowd via radios.

Shutters snapped and keyboards popped with the beginnings of what would become the most covered and photographed single-event national disaster to date — sparking publication of three books just weeks after the disaster: “The Quake of ’89,” by The Chronicle; “15 Seconds,” by Tides Foundation; “Earthquake 7.1,” by LTA Publishing Co. with United Press International. All three quake books are still available on Amazon.com, along with many others published months later.

The Earthquake From Above

John Crayton, captain of the Goodyear blimp filming for ABC-TV, floated above Candlestick Park at 5:04 when he suddenly felt odd vibrations and lost the TV link 2,000 feet below. He thought someone below had tripped over a cord and pulled a plug. “A director could lose his job for that,” he told The Chronicle.

Crayton then saw a green flash under Interstate 280 — transformers exploding. The blimp regained contact with a ground technician who simply said: “Earthquake!” As the blimp sailed from the stadium, the crew filmed and photographed one of the most dramatic disaster sites: “The Bay Bridge was just broken. The top deck was down into the lower one. I thought, ‘Oh, my God,’” Crayton said.

“Gradually, it began to sink in: Today, there are people dead. People homeless … the fires are not fireworks, and this is not a movie,” author Herbert Gold said in The Los Angeles Times.

Chronicle columnist Art Hoppe internalized the disaster. “I relished the exhilaration that escape from danger brings. The routine of my days had been shattered. How young and vital I felt. How more precious life becomes when others are losing theirs.”

Journalists Hit the Street

Often at great risk to themselves, “photographers instinctively recorded the casualties and documented the horror, despair, heroism and hope of the day,” Maureen Healey and Susan Wels reported in “15 Seconds.” Photojournalists were “witnessing a natural disaster, the full toll of which would not be known for weeks. Before their job was over, they would all be touched by the grief and human suffering they were capturing on film.”

Freelance photographer Ron Tussy, on assignment for Newsweek, saw the Marina District fires through binoculars from his Sausalito home across the Bay. Soon, he was zipping across the Golden Gate Bridge toward the flames.

“The further I went into the area, the more grotesque the buildings looked,” Tussy told “15 Seconds.” Firefighters were “desperately trying to hook up hoses to hydrants and nothing but mud was coming out. I heard one say, ‘We might lose this whole part of the city,’ and visions of 1906 earthquake and fire photos swept over me.”

Journalists encountered hazards at every turn in the Marina. “On one corner a gas main had broken and was spewing gas and mud 10 feet into the air. A firefighter shouted ‘Go back!’ The whole block’s gonna blow,’” Connie Ballard reported in The Chronicle.

“The Red Cross opened 30 shelters and hosted 5,000 people from San Francisco to San Jose including commuters stranded by collapsed bridges and closed freeways,” Robert Strand, UPI, reported. “Near the Interstate 880 freeway collapse in Oakland, hundreds of volunteers appeared with forklifts, generators, searchlights, and other equipment to join efforts to pull survivors or bodies from the debris.”

How Journalists Viewed the Disaster

“There was a certain wildness in the air, a ‘tomorrow we die’ attitude based on the unspoken awareness that the Earth could open up and in the next instant swallow it all — from the baroque palaces of Nob Hill to the gaming houses of the Barbary Coast,” columnist Herb Caen wrote in The Chronicle. “We realize afresh the joys and dangers of living here, and we reaffirm our belief that it is worth the gamble, however great.”

“There was no greater betrayal than when the earth defaults on the understanding that it stay under foot while we go about the business of life,  which is full enough of perils as it is,” Chronicle reporter Jerry Carroll said.

which is full enough of perils as it is,” Chronicle reporter Jerry Carroll said.

“Inherent in the national coverage was a sensationalistic approach,” San Francisco Examiner reporter John Dvorak said. “By putting the news anchors in front of that same collapsed apartment building in the Marina, one would think it was typical of the whole city. It was a pathetic ratings grab, which worried people needlessly.”

“People in the neighborhoods then started getting together and turning to each other for support,” Randy Shilts said in The Chronicle. “Neighbors who’d never met each other started finding out who their neighbors were and began to do what neighbors are supposed to do, which is to take care of each other.

10,000 Images for a Unique Book

Ron Tussy, among numerous other journalists, spent the next four post-quake days covering the rescue at Interstate 880, the devastated Marina, and the Santa Cruz destruction.

Exhausted, drained, horrifying images burned into his psyche, Tussy decided to do something different from other journalists — more than just reporting the disaster. He conceived a plan to actually help the victims. “I wanted to get other photographers nationwide to donate their pictures to make a book to benefit earthquake victims.”

Tussy recruited Doug Menuez, another photojournalist, and David Cohen, director of the “Day in the Life” photo book series. Cohen said, “Great idea,” but emphasized the need for extreme speed to generate continued interest. With dozens of volunteers, 10,000 photos to select from, and several rounds of intense text and photo editing, the 120-page “15 Seconds” was published in just a month, its profits going to quake victims.

Major Northern California newspapers, AP and UPI wire services, and national news magazines all contributed film, negatives and even a few photo editors to the book project. Bay Area organizations donated editing equipment and office space to the project. Several large corporations financially sponsored the publication in its entirety.

Of the many photojournalists involved, Timothy Baker, Santa Rosa Press Democrat, may have most effectively expressed the human need to help. “As photojournalists, you think you’re doing a service when you photograph a tragedy. But “15 Seconds” was a way to make up for all the times I wanted to put my camera down and lend a hand. It was a healing process for all of us.”

Earthquake Time Is Real Time

Stephanie Salter, Examiner columnist and reporter, put the massive Loma Prieta earthquake into perspective:

“A few days after the main shudder, they told us the quake had lasted only 15 seconds. But that is in real time. Earthquake time isn’t real time.

“Or maybe the truth is, earthquake time is the most real time of all, a time when all the bull ceases and the preciousness of life is understood most acutely. In earthquake time, nobody gives a damn about a rebounding Dow or the Giants being down in the World Series, two games to none. In earthquake time, the bashed-in fender of a new car is invisible, a broken leg is but a twitch, and the richest people in the world are the men, women and children who have someone to hold onto until the shaking stops.

“The big one of Oct. 17, 1989, was not an event we can or should forget or try to ‘get over.’ It was a traumatic experience that started in the depths of the earth and wreaked damage all the way to the depths of the psyche. The quake and its unscheduled but inevitable big encore are simply facts of life we must learn to live with — as vigorously, humorously and gracefully as our combined human resources can allow us to.”

Jim Toland is a retired San Francisco Chronicle staff editor, retired San Francisco State journalism instructor, published novelist, and Army veteran. A native San Franciscan, earthquakes are, to him, just a normal part of life.