In October 2014, the San Francisco Bay Guardian shut its doors after 48 years of publishing under founder Bruce B. Brugmann’s adage that “It is a newspaper’s duty to print the news and raise hell,” a 19th century motto from the Chicago Times.

By then the paper, a beacon of San Francisco’s progressive wing, was under new ownership, but the staff hadn’t lost the spirit of its founder. As a final tribute, former staffers crowdsourced $26,000 in donations to underwrite a commemorative edition.

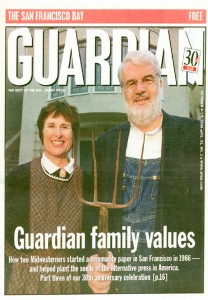

Digital copies of the final issue can be found here. Below is the story of the Guardian’s founding and evolution by Brugmann and his wife, Jean Dibble, who ran the business side of the paper.

By Jean Dibble and Bruce B. Brugmann

In October 1966, we founded the San Francisco Bay Guardian with the rather naïve idea of challenging the local Examiner/Chronicle joint operating newspaper combine with a good local entrepreneurial newspaper. We were each just 31 years old and we had no idea what we were getting into in San Francisco, the place that Warren Hinckle called the Bermuda Triangle of publishing.

We had the essential ingredients of the entrepreneur: the power of innocence and not knowing any better. But we also had a vision, good Midwestern survival values, and a branding line that caught the spirit of what we were trying to do: “It is a newspaper’s duty to print the news and raise hell,” the motto of the old Chicago Times.

Somehow we thought that if we could just get the paper going — this was San Francisco in 1966 and the world was ready to explode with Vietnam, the Summer of Love, and sex, drugs, and rock and roll — we would make it go, come hell or high water.

Well, after going through hell, high water, and endless dramas, we and the hundreds of staffers who worked for the Guardian through the years pioneered a new form of competitive journalism: the alternative press. There are now alternative newspapers in most cities throughout the country.

The Guardian was the first newspaper designed expressly as an alternative to the local daily monopoly and we strongly emphasized the “alternative” label. The daily papers looked at the world from the top of the Transamerica Pyramid down, while the Guardian looked at the world from the bottom up. We created thousands of new jobs through the years and launched hundreds of careers in journalism, graphic design, marketing, sales, small business, and political and journalistic activism. And we inspired scores of entrepreneurs.

To raise capital to start the Guardian, we needed a prospectus and a sample issue. Jean had business experience, including with San Francisco firms Matson Navigation and Hansell Associates, and was a graduate of the Harvard Radcliffe Program in Business Administration. So she prepared the financial part of the prospectus that we used to raise money. Bruce contributed the editorial vision.

Bruce had lots of newspaper experience starting at age 12 writing for his hometown newspaper in Rock Rapids, Iowa. Later, he was editor of his college paper at the University of Nebraska, reporter for the Lincoln Star, graduate of the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism, Korea bureau chief for Stars and Stripes, and a Milwaukee Journal reporter.

During the planning stages of the Guardian from 1964 to 1966, Bruce covered environmental battles for the old Redwood City Tribune. Writing the prospectus set the pattern for how we would work together for 46 years, more or less harmoniously. We had complementary skills. Jean handled the business side and Bruce handled the editorial side and was responsible for raising the money. We split the publishing duties. Bruce liked to say that Jean handled the bank while he handled PG&E.

We raised $45,000 to start the paper, but that was not nearly enough. By Christmas, we were out of our initial capital and needed to raise more. Bruce was unable to pay himself a salary to provide for the family, so he taught journalism and writing courses at UC Berkeley, CSU-Hayward, and UC extension in San Francisco. For several years we published a new issue only when we were able to pay the bills from the previous issue. It was not until 1972 that we were able to publish regularly, every two weeks. In 1975, we began weekly publication.

In the early days, we would put the paper together at the printer, do the press check, and then Bruce would load the papers into the family Volkswagen bus and drive around filling newsracks.

Our first editorial election endorsement in November 1966 was for Gov. Pat Brown over Ronald Reagan for governor. The editorial was eerily prophetic: “The repudiation of Brown and the election of Reagan would mean that a generation of progressive legislation – in Medicare, in education, in welfare, in conservation, in water resources, in bringing to account the dreadful problems of growth, population and sprawl – would be in jeopardy.”

The Guardian was an early and strong opponent of the escalating war in Vietnam and made a special mark with a local investigative piece disclosing how a small group of Bay Area morticians was competing vigorously to corner the undertaking market on bodies returning from Vietnam.

At the height of the Vietnam War draft, the Guardian produced the first of its trademark investigative stories that had local and national impact, sparking reform and serving as a model for investigations elsewhere. “The Draft Boards – a Guardian Probe” blasted open the secret draft boards and published, for the first time ever, a list of draft board members that included their names, addresses, and occupations, along with a map showing that members didn’t live in the districts from which they were sending mostly poor and non-white young men off to war. The story created a national sensation and led to resignations, a blizzard of anti-draft lawsuits, and ultimately, reforms in the Selective Service system.

In June 1968, the Guardian published “Manhattan Madness,” the first of a long series of stories and cost-benefit analyses defining a key struggle that the Guardian helped define: the Manhattanization of San Francisco. In 1971, the Guardian published the landmark study that demolished the Chamber of Commerce’s central argument in favor of Manhattan-style highrises, showing that the skyscrapers gobble up more in city revenue than they return in taxes. The study was incorporated into a Guardian book, The Ultimate Highrise, with superb graphics by Art Director Louis Dunn.

In November 1986, after a 15-year Guardian editorial campaign and four unsuccessful initiatives, San Francisco voters passed the slow-growth Prop. M. It effectively stopped the high-rise boom and imposed the strictest growth controls in any American city. That was one of many important causes the Guardian championed over the years.

In early 1969, Joe Neilands, a UC Berkeley biochemistry professor, handed Bruce a big story he’d written about Pacific Gas & Electric. Bruce quickly saw that, if it checked out, it would be a blockbuster. “Why are you bringing this story to the Bay Guardian?” Bruce asked Joe, who replied, ”Bruce, if you don’t run this story, nobody else will.” So in March 1969, we ran “How PG&E robs SF of Cheap Public Power.” Thus began the Guardian’s famous campaign to enforce the federal Raker Act and bring the city’s cheap Hetch Hetchy power to San Francisco.

Why, we’ve often been asked, after all these years, do you keep pounding away at the PG&E Raker Act scandal? The answer: because it is the biggest and most costly corruption story in San Francisco history. To this day, PG&E continues to corrupt the political system, the media, and the state regulatory system, as the recent scandals of the California Public Utilities Commission show.

Openness and transparency in local government was another important Guardian crusade, starting in early 1987 when we exposed how taxpayer money was funding the League of California Cities and other groups that were lobbying for more secrecy in local and state government. Our ongoing coverage helped create the movement that reformed state open meetings and records laws and created the San Francisco Sunshine Ordinance and Task Force in 1993, the first and best open government law in the country.

The years sped by and the Guardian’s influence increased, especially in electoral politics and the arts. As our revenues grew in the late ’80s and the ’90s, we were able to increase the size of the staff and the paper. We started our annual Best of the Bay edition in 1974, an idea and format copied around the world. Our annual Goldies awards and ceremony (Guardian Outstanding Local Discoveries) recognized emerging talent in all the arts. Our Small Business Awards and ceremony recognized local businesses that made significant contributions to the community. We were early supporters of gay rights and published our first Gay and Proud issue in 1974. We helped build the Gay Pride Parade and helped to make Harvey Milk the first openly gay elected official in the country.

We wanted to set up the Guardian as an enduring community institution. However, like other small newspapers, the Guardian faced a maelstrom of problems. We always struggled to pay our staff a decent wage and still cover our other expenses. The 2008 recession made it particularly difficult, for us and our base of small retail advertisers. Despite the Guardian’s strong online presence, we lost both advertisers and readers to the Internet, including losing our lucrative personal ads and other classifieds to Craigslist.

The Guardian was also the victim of a savage predatory pricing attack that started in early ’90s when the New Times chain from Phoenix, Ariz., bought the SF Weekly. New Times/SF Weekly sold ads below cost with the expressed goal of putting the Guardian out of business. We had no alternative but to file a predatory pricing lawsuit or slowly bleed to death.

The Guardian won its suit in Superior Court and subsequent appeals, establishing through discovery documents that the New Times had intentionally lost millions of dollars to steal our market share. The legal victory, which updated and reaffirmed California’s Unfair Practices Act, was a major victory for independent media and small businesses under threat by corporate abuse

The Guardian won a significant monetary award, but it was not enough to cover our heavy debts and keep the Guardian going with its steadily declining revenues. So in 2012, we reluctantly decided to sell the paper to the San Francisco Media Co., headed by Todd Vogt, a Canadian publisher who also owned the SF Examiner.

We thought that he had a good chance of making the Guardian successful because the Examiner had its own presses in San Francisco that could save on the press bill. He also had space for the Guardian employees in his office. He promised to take the staff and continue the Guardian tradition. Alas, it didn’t quite work out that way.

We feel terribly sad about the demise of the Guardian. But we are so grateful to the staff who hung in with us through the ups and downs and for the support of our advertisers, readers, and almost 400 donors to the Save the Guardian Indiegogo campaign, which enabled us to print this issue and help preserve the archives.

Let us say for the record that the Guardian staff put out one helluva of a newspaper under challenging conditions for almost half a century and we always stood for the motto we carried on our masthead for every issue: “It is a newspaper’s duty to print the news and raise hell.”

We did so with zest and pride for the righteous causes and key issues of our time.