Don Barksdale was the “Big Daddy” whose radio show brought rhythm and blues to the “San Francisco Bay Area Negro Market.” Rosko ad-libbed record intros in rhymes as he spun soul sounds. In her late-night slot, Jeannie was billed as “the only female personality in Bay Area Negro radio.” They were part of an array of African American personalities and pioneers who made their mark on the airwaves.

By Ida Mojadad

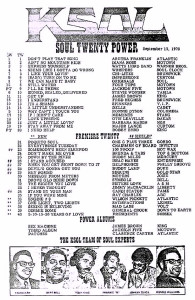

Long before Michael Jackson broke the crossover music color barrier, Motown and R&B artists were heard mostly in the Bay Area on “soul” radio stations like Oakland’s KDIA and San Francisco’s KSOL. These call letters—familiar in the 1960s and into the 1990s—were not only celebrated for their music but for community involvement and service.

Black artists like James Brown, Ray Charles, Aretha Franklin, Diana Ross and a range of vocal groups could be heard on Top 40 AM stations like KYA, KEWB and KFRC during the mid-1960s—but only if their records hit the pop charts. For two decades, however, KDIA and KSOL reigned supreme for Bay Area black radio—giving rise to media icons like Belva Davis, Sly Stone, George Oxford and John Hardy.

At a time when black artists and broadcasters were not yet fully embraced, KSOL (1450 AM) and KDIA “Lucky 13” (1210 AM) often hired announcers and managers from each other.

“If you wanted to hear anybody of color, you had to listen to KDIA,” said Diane Blackmon, the station’s first female disc jockey. “It was segregated radio.”

“KDIA was always committed to the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Area as far as community involvement,” said its former program director Johnny Morris, who started at KSOL at age 15 and later moved on to KDIA.

Morris recalls working with the Black Panthers on community issues while KDIA personalities represented the station at local events like the “Juneteenth” Festival, a neighborhood celebration held in San Francisco’s historically black Fillmore District. Juneteenth celebrates the abolition of slavery in the United States.

KDIA’s outreach programs, like their Black Woman of the Year Awards and voting awareness efforts, earned the station the 1963 Freedom Foundation Achievement Award for its work as a community service medium.

Morris credits station managers Bill Doubleday of KDIA and Tom Johnson of KSOL as the two people who played an integral role in building community focus and putting both stations on the map. He also praised them for their creativity and innovation in radio.

Behind the microphone, the stations made room for editorial commentary and talk shows like KDIA’s “The Belva Davis Show,” marketed as the “Only Women’s Show in Local Negro Radio.”

Roland Porter and “Big Don” Barksdale also hosted their own KDIA shows playing R&B music and relaying wire news, sportscasts, weather reports and hourly news features relevant to the community.

Sly Stone of the legendary Sly and the Family Stone music group began as a disc jockey on KSOL,

working with Morris in 1964. Stone, who held some 40 percent of the target audience, also switched over to KDIA a few years later, when his music career started to take off.

As KDIA program director, Morris felt he should be more open-minded for the sake of local artists, like Oakland’s Marvin Holmes and The Uptights and Vallejo’s Con Funk Shun.

“It was a label game,” Morris said about airplay. “If it sounded good enough, I gave it a chance.”

However, the radio crew was still able to cross paths with Prince, Aretha Franklin, The Jackson 5, Smokey Robinson, The Temptations and others.

In 1974, KDIA took a different kind of chance with the hiring of its on-air personality, Diane Blackmon, as the first female broadcast engineer in California.

“That was a milestone there,” Morris said. “There were no female DJs or engineers in any station. It just raised the bar.”

Blackmon credits Morris, a longtime friend, for teaching her everything she knows about radio. “I was always very proud of her,” he said.

“The highlight was being a regular girl from Vallejo who had an opportunity to be on the radio in my hometown,” Blackmon said, “and being able to hang out and interview and work with a lot of entertainers I grew up idolizing.”

But Blackmon felt the pressure of representing all females in the occupation and the challenge of being taken seriously while susceptible to jokes and remarks. She recalled a time when the station went silent under her watch and she couldn’t get it running again for hours, the kiss of death for a radio station.

“Johnny Morris came in and turned to me and said, ‘If it was a stove, you’d know what to do,’” said Blackmon. “Those types of little things kind of hurt my feelings.”

While emphasizing that the good times outweighed the bad, Blackmon cited low wages and lack of career mobility as the impetus, in 1984, for starting her own business, Blackmon Entertainment Media, with former husband Lee Bailey. For 30 years, she’s been the overseer of everything she does, while still in the business of managing radio stations.

“I got out,” Blackmon said of her radio staff position. “I kept bumping up against the glass ceiling.”

Newer women staffers, like Leslie Stoval, would remain at the station when Blackmon left KDIA in 1983—at least until the station underwent major changes. Still others noted KDIA’s strong signal and saw a different opportunity with that reach.

Adam Clayton Powell III acquired KDIA in 1984 and changed its call letters to KFYI and its format to all news. To his surprise, the new format lasted less than a year when previous owner, Ragan A. Henry, bought it back and returned its focus to music.

“Listeners are never pleased when something they listen to changes,” Powell said. Still, Powell was proud of the in-depth coverage of local and regional issues KFYI covered—especially an investigative series on San Quentin Prison.

After the switch back to a music format, KDIA ran through the ownership of future San Francisco Mayor Willie Brown and Oakland Mayor Elihu Harris before eventually transitioning into the Christian talk radio format it is today.

KSOL ran into turbulence as well with a 1970 civil rights suit filed by five former DJs alleging they were fired because they were black. The suit stated that they were terminated upon the station’s switch from “black oriented” to “middle of the road” mainstream music programming. Owners John F. Malloy and Alan P. Shultz settled out of court, denying discrimination.

Eventually, rival KMEL’s switch to an urban contemporary format shook the influence of KSOL, which called it quits in 1992. Popular KMEL helped advance the careers of major hip-hop and R&B artists in the 1980s and ’90s.

Blackmon noted that while large corporations have invested in, and profited from, African American artists, black music audiences are “still not valued”—and there is much work to do.

“It’s a shame that’s there’s no more strong local black radio in the Bay Area, ” said Blackmon. ”KDIA had community interest at heart.”

Ida Mojadad writes for SF Weekly and, armed with a crisp new B.A. in Journalism from San Francisco State, will be seeking a full-time position in media.